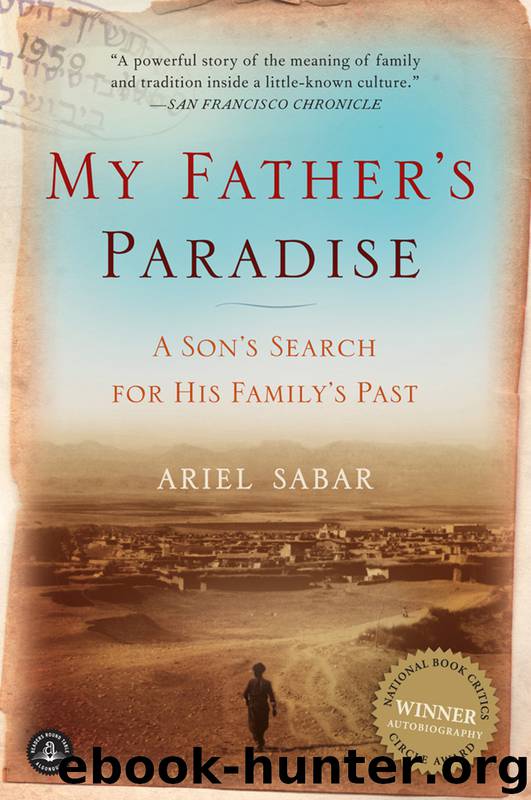

My Father's Paradise by Ariel Sabar

Author:Ariel Sabar [Sabar, Ariel]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Algonquin Books

Published: 2008-06-03T04:00:00+00:00

Yona, right, recording “Mamo” (Uncle) Yona Gabbay’s stories, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, circa 1963.

PROFESSOR POLOTSKY’S INTEREST was linguistics: what an informant’s words could reveal about Neo-Aramaic grammar, syntax, and its ties to other languages. Content was virtually irrelevant, the speaker’s toileting habits beside the point. What drew a linguist to storytellers wasn’t their stories but their long-windedness, their ability to rattle on for hours. But how could my father listen to this bearer of his own culture and not be drawn in deeper?

Last year, at the Israeli National Archives, I was leafing through a 1964-65 Hebrew University catalog and found a black-and-white photo of my father and Mamo Yona in the recording booth, over the caption “Research in Ethnic Dialects.” Mamo Yona, looking as if he had just emerged from forty years’ wandering in the desert, is speaking into the microphone and gesturing with the bunched fingers of his right hand. My father, buzz cut, and in a crisp white dress shirt and slacks, has his back to him as he works the reel-to-reel. You would never know they once breathed the same air or drank the same river water.

But keeping up appearances was harder than my father expected. One day in the early 1960s, he clicked on the recorder and made an unusual request of the old man. “None of the usual fables today, Mamo,” my father said. “Please, just tell me, if you would, the story of your life.”

There was a long pause, and then a deep breath.

“Dear audience,” Mamo Yona began, “once, when we were very poor …”

Mamo Yona didn’t stop until his autobiography reached the very day my father entered his life. “One day, I look, I see this Yona come looking for me, saying, ‘Uncle Yona.’ I said, ‘What is it, uncle’s dear?’ He says, ‘Get up, let us go, quick!’ ‘Where?’ He says, ‘Get up! Let us go to the language lab. Tell us a story, we’ll pay you five liras per hour.’”

It was soon clear that Mamo Yona had lost none of his wiles: “One time I told stories, and Yona gave me my earnings,” he said, well aware that my father was listening through a headset in the next room. “Another time, I told stories for four or five days, and he gave me my earnings. Lately, I’ve been telling stories for a few days, but he hasn’t yet paid me. We’ll see. Whatever he wishes, we’ll take him at his word.”

My father had to smile: Mamo Yona was back at his old game, a hustler softening up another mark.

Mamo Yona was 103 when he died, in Israel, in 1970. He lived until the end in a corner of his son’s apartment. The recordings would win Mamo Yona a small kind of fame, at least within the world of Semitic linguists and folklorists. A photograph my mother took of him would grace the jacket cover of my father’s 1982 book on the folk literature of the Kurdistani Jews. A few years ago, my

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Civilization & Culture | Expeditions & Discoveries |

| Jewish | Maritime History & Piracy |

| Religious | Slavery & Emancipation |

| Women in History |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31348)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30946)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30905)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16656)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(13071)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(11914)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10914)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(4549)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(4427)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4408)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4287)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(3853)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(3775)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(3646)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(3575)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(3525)

Hitler in Los Angeles by Steven J. Ross(3446)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(3343)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3267)